Providing a prognosis without a diagnosis is like giving a sentence without a trial. Getting the right diagnosis requires the right assessment…

There is an idea circulating that the prognosis a healthcare practitioner provides is more important than the diagnosis. I would argue that we cannot determine the prognosis without first formulating a diagnosis. While the prognosis can and should be what matters to the patient, the prognosis itself is diagnosis-dependent.

We should not give into the temptation to just say, “it’s mechanical, you lack mobility, its just pain, or we don’t know what’s going on but here’s your prognosis!” We need to re-evaluate what the purpose of a diagnosis is for conservative healthcare practitioners and why providing one is a duty you owe to your patient.

So what’s in a diagnosis? Diagnosis comes from the Greek dia “apart” + gignoskein “to learn, to come to know,” or to “know thoroughly.” So in the true meaning of the word, we just need to know what’s going on with the patient in as much detail as possible to discern it from other patient states. While the patho-anatomical model often fails to encompass the full clinical picture of our patients, we also need to consider why we need a diagnosis in the first place. I would postulate the following reasons to label something with a diagnosis:

- Treatment – Often (especially if you get it right!) the diagnosis determines the best course of treatment and helps the practitioner determine what needs to be done, including the ability to recognize consistent patterns that will guide future similar cases.

- Prognosis – As stated above, you cannot know how long it will take for someone to get “better” without knowing what they “have.” More on this below.

- Communication – Both to the patient and between healthcare practitioners (because collaboration is important!).

- Research – How can we study a “disease,” “dysfunction,” “pain syndrome,” or other entity if we don’t articulate what “it” actually is?

I can think of individual cases where these arguments may not hold up. This is especially true in the musculoskeletal domain. In traditional medicine, we can take a swab and culture a particular pathogen that is causative for a specific disease and its associated signs and symptoms. However, we all know that you can’t swab a painful patellofemoral joint and use it to determine the relationship between the knee pain, hip and foot function, injury history, pain perception, co-morbidities, and all of the other associated findings that come with making a clear, useful musculoskeletal diagnosis.

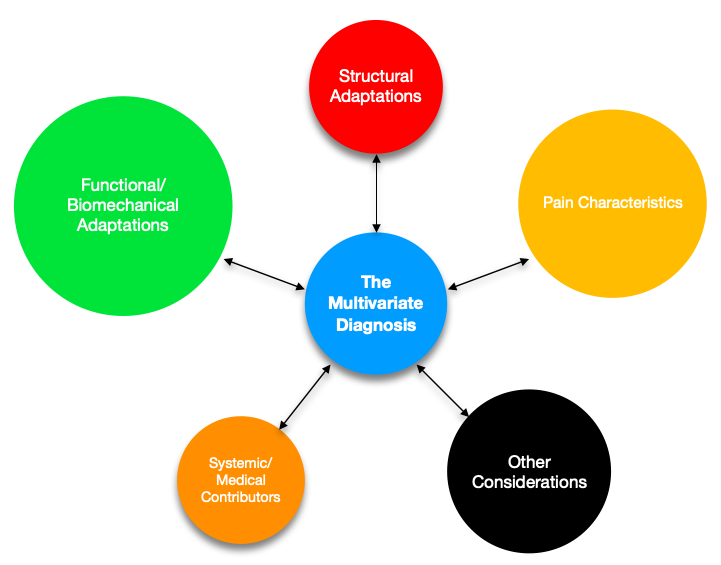

Because of this, I prefer formulating a diagnosis that is representative of all the clinical entities I intend to address. To do this, we can create a “Multivariate Diagnosis,” which describes all of the entities (that we are aware of), which may be contributing to the “thing” that brought your patient to see you. Quite often it is pain, and the limitation exists where the patho-anatomical model fails to explain the full clinical picture (i.e. this structure makes this hurt) or provide a satisfactory outcome. However, this does not mean the the structural patho-anatomical elements have NO involvement. I will discuss the Multivariate Diagnostic approach using an example of a patient who presents with “patellofemoral pain.”

| CATEGORY | POSSIBLE FINDINGS |

| Structural Adaptations | Chondromalacia, PFJ arthrosis |

| Functional/Biomechanical Adaptations | Patellar tracking issue, hip weakness, trunk lean, excessive PFJ joint loading activities |

| Pain Characteristics | Peripheral nociceptors, central tendencies, pain beliefs |

| Systemic/Medical Contributors | Diabetes, smoking, inflammatory arthritides, hormones, diurnal variations etc. |

| Other Diagnostic Considerations | Other regionally dependent injuries, psychosocial confounders, state-variability |

Figure 1. The categorical contributors of the Multivariate Diagnosis.

It is important to recognize the dynamic and variable nature of each of these categorical features. Some of these findings are modifiable, some aren’t. Some of these we treat within a session, some over multiple sessions, and some not at all (even though they may be contributing!). There are complex interactions that occur within and between categories and the relative contribution of each can also change over time, which in turn should modify your treatment plan and your prognosis.

Figure 2. Example of variable magnitudes of diagnostic contributors

Having these interactions in mind will provide clarity when a typical “condition” (patellofemoral pain) doesn’t respond the same way in one patient as it does in another. We should not treat our patients like “pain dummies” that we just coax out of pain (through treatment, exercise, pills, etc). We should also be considering the long-term effects on their physiological and psychological states. This line of thinking goes beyond trying to fix a structure (surgery or loading), improve biomechanics/function (manual therapy or exercise), or relieve pain (modalities, positive encouragement, education).

As stated at the beginning, the prognosis is dependent upon the diagnosis. And the multivariate diagnosis comes from a thorough and detailed assessment. In the AMA seminars, our assessment paradigm removes the constraints in traditional diagnoses and allows for a more complete picture of athletic movement. Come join us at one of our seminars to learn more!

Patrick Welsh, BSc, DC, FRCCSS(C)

Co-Director of AMA